Amortized Bayesian Full Waveform Inversion and Experimental Design with Normalizing Flows

Image 2023 abstract

OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE

Probabilistic approaches to Full-Waveform Inversion (FWI), such as Bayesian ones, traditionally require expensive computations involving many wave-equation solves. To reduce the computational burden at test time, we propose to amortize the computational cost with offline training. After training, we aim to efficiently generate probabilistic FWI solutions with uncertainty. This aim is achieved by exploiting the ability of networks (i.e Normalizing Flows) to learn distributions, such as the Bayesian posterior. The posterior uncertainty is used during training to optimize the receiver sampling.

METHODS, PROCEDURES, PROCESS

Normalizing flows (NFs) are generative networks that can learn to sample from conditional distributions, here our desired Bayesian posterior p(x|y) where x are earth models and y is seismic data. To train NFs, we require training pairs of those earth models and seismic data. We use pairs from the open source dataset OPENFWI. The earth models are .7km by .7km and the seismic data is simulated with 5 sources with 15Hz frequency and 20dB noise. We use the CurveFault_B dataset from OPENFWI that contains 55k pairs and split the pairs for training, validation, and testing 90%/5%/5% respectively.

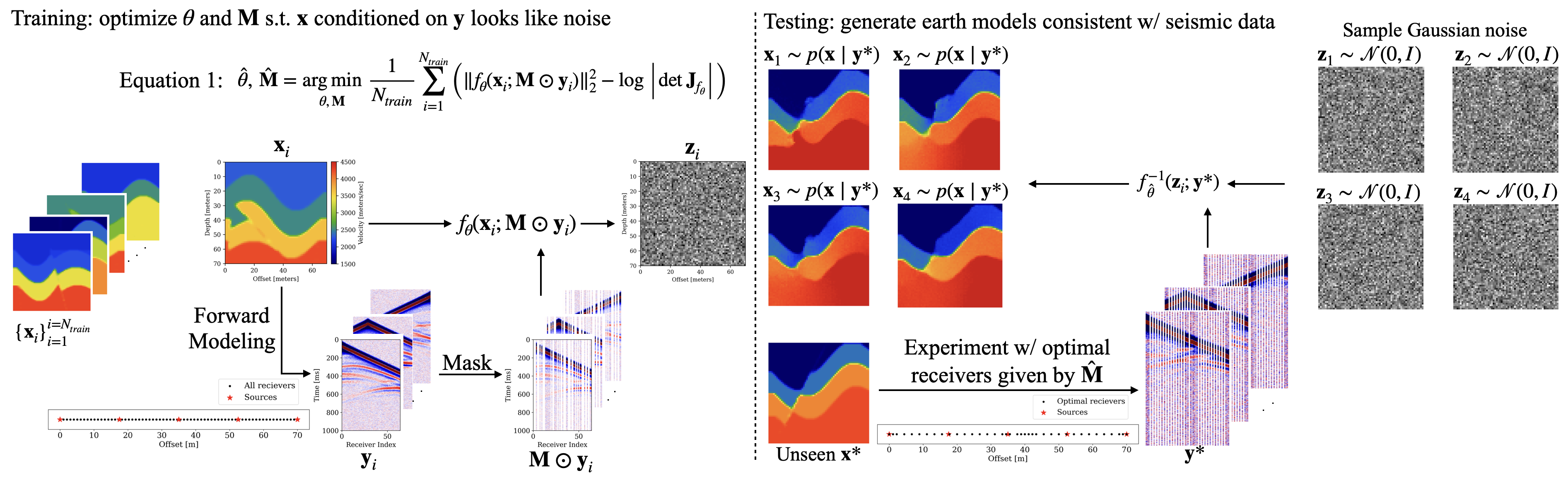

To learn to sample from the conditional distribution, the network learns to transform the earth models to Gaussian normal noise while conditioned on the acoustic data. By construction the network is invertible, thus after training we sample Gaussian normal noise and apply the inverse network to generate samples from the posterior, again conditioned by the seismic data. The training and testing processes are illustrated schematically in Figure 1.

The NF training objective has been shown to be equivalent to maximizing the information gain, as defined by Bayesian optimal experimental design (EOD), of the conditioned data. Thus, we propose to jointly optimize for a receiver sampling mask M and the network parameters during NF training to simultaneously learn the Bayesian posterior and the optimal minimal receiver geometry.

RESULTS, OBSERVATIONS, CONCLUSIONS

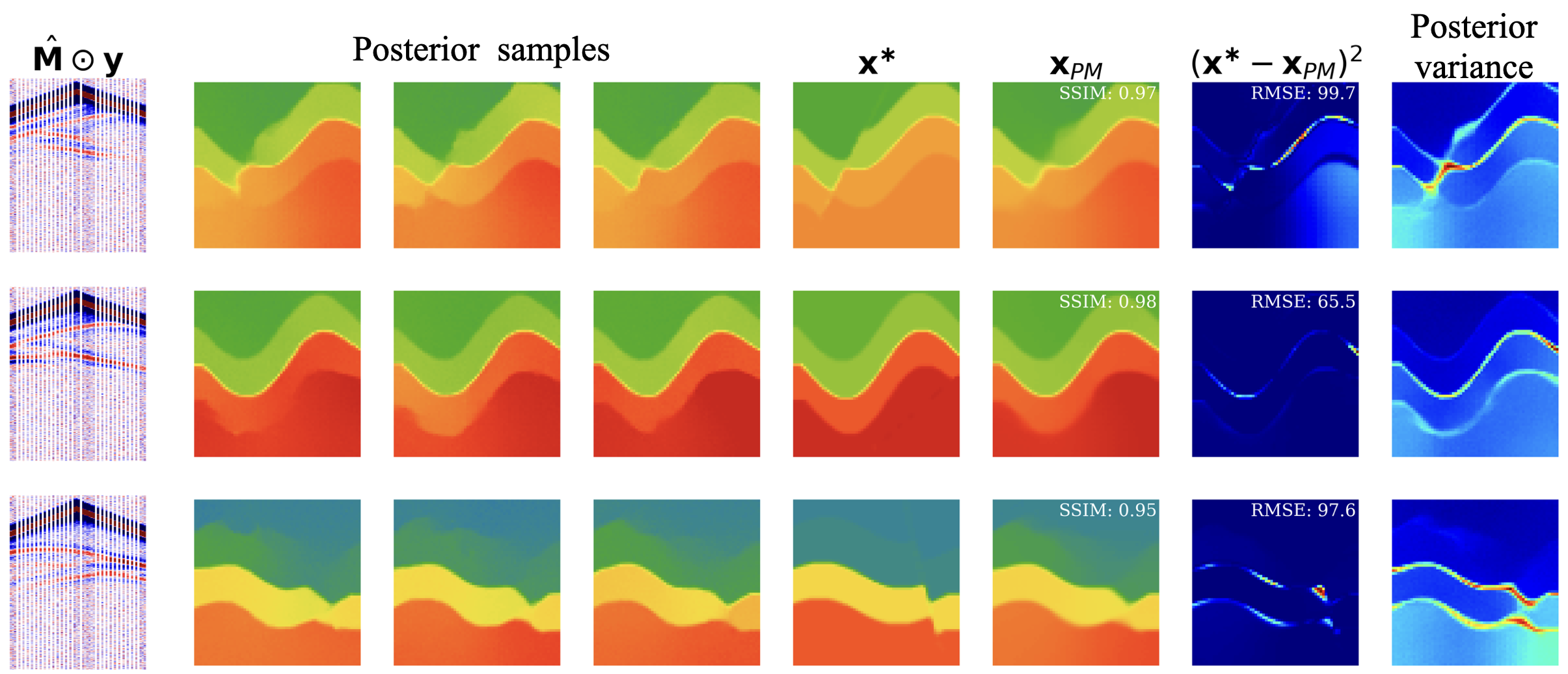

After training, our method generates posterior samples at the cost of one network inverse pass (10ms on our GPU). Seen in Figure 2, the posterior samples are realistic earth models that could plausibly correspond to the seismic data. The variations between the posterior samples are due to the FWI problem being ill-posed and because of noise in the indirect observations at the surface (20dB noise). To study these variations, we take the sample variance as our uncertainty quantification (UQ). We observe that the UQ is concentrated on steep and deeper structures. Both these types of structures are difficult to invert for with FWI showing that our UQ correlates with the expected error making our UQ realistic and interpretable.

To make a single high-quality solution, we take the mean of the posterior samples. This posterior mean \(\mathbf{x}_{PM}\) shows high-quality metrics that surpass OPENFWI benchmarks while producing Bayesian UQ not available with the OPENFWI benchmarks.

The optimal receiver sampling obtained by our method (black circles in “test” portion of Figure 1) are the traces that the network has learned to select to best inform the inverse problem.

Our method is amortized since the aforementioned computational debt of probabilistic FWI is paid by modeling the training pairs (x,y) and the cost of training the network. After these costs are incurred offline, our method can efficiently sample from the Bayesian posterior for many unseen seismic datasets without wave-equation solves.

SIGNIFICANCE/NOVELTY

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of normalizing flows applied to amortized FWI with Bayesian uncertainty quantification. We also showed a practical application of the uncertainty towards optimal experimental design of acquisition geometry. While the open source dataset used has small models, NFs are memory efficient due to their intrinsic invertibility and are set to scale to realistic sized problems and field datasets.